A Quiet Dignity

* Pictures courtesy of Johann, Suresh and me. *

In the Nilgiri mountains within the Tamil Nadu district of South India, there live a people that date themselves back to the conquering heroes of Alexander the Great and the Macedonians.

They speak a language that has lilting tones and sibilant sounds that are strangely reminiscent of the Lakota nation in North America. They wear their hair in single or double plaits, drape hand-embroidered shawls like the Romans of old, and worship the buffalo. They revere nature and abhor warrior-like activities, but live in a small but communal world where a woman can be a wife to many men, and a man can be a husband to many women.

These are the Toda people. They are indigenous to these hills. Despite seeing their own leave their community boundaries and never return, despite watching a population age and their kind dwindle down to around 1,500 people, they still walk erect with pride and do not forget their stories and teachings of old. They speak Tamil to outsiders, tell them of the Toda heritage, but speak to each other in their own secret language that echoes their unique identity that they are still fiercely trying to protect.

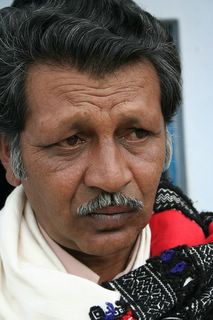

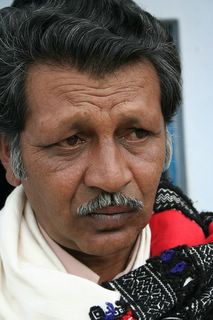

Chief tells us, in his deep voice, that there are not many Toda left. Many young people have left, to pursue what they think is a better life outside their village boundaries.

Many young people have left, to pursue what they think is a better life outside their village boundaries.

But don’t they keep in touch? Visit you?

Once they leave us, they have left us forever.

It is sad that there is no turning back. I imagine I heard in his voice, in the strong yet quiet voice of this village headman, that it breaks his heart when they leave, because he knows how hurtful it is to not be part of your people anymore, how painful to see them outside and treat them no more than strangers.

Their homes feature an elliptical roof – historically because the Toda would bend the flexible reeds and branches to make roofs, and has since become an architectural feature unique to their people. Their homes are now concrete, a modern convenience that still pays homage to their simple lives by being no bigger than a shipping container.

When Chief invited us inside, we stepped in barefoot quietly in reverence. He showed us with pride, pictures of his family, his people – some living in other areas of India, gathering for tribal celebrations in their full regalia. Some of these pictures were old and dogeared. Others were clearly pictures taken by visitors that were left with him as momentos.

He took pains to explain each picture – this is a marriage ceremony, this man is a chief over in this other village. The words were few, but the feelings ran deep. I imagine this man knows in his heart that he could be the last of his family to still have 30-year-old pictures of millennia-old rituals, explaining age-old customs to young visitors.

The walls were solid and smooth, yellowed and bare, except for faded pictures in old frames, and the symbol of the buffalo horn, placed high in a position worthy of respect. There was a bleak sadness to this spartan house – but you couldn’t help but be filled with admiration for the dignified way Chief, and his wife, speak of their people, their efforts to survive, and live meaningfully to preserve their heritage.

The small house opens into a spacious cement frontyard, where Chief’s aunt (I think) smiles at us. An irresistible photo opportunity.

The front yard was the start of the true world of the Toda – green fields marked by solitary stones, holy spiritual space bound by pieces of ancient rock. It’s okay, says Chief. Female non-believers can walk past the stones, we do not mind. Toda women know to stay outside these rocks.

There are two temples, probably musty with old on the inside, full of mystical and ancient energies that are shut behind stone walls with hand-carved symbols of the sun, the moon and the stars. We do not get too close – Chief says non-believers are not permitted past the rock wall immediately surrounding the small temple. We don’t get closer – the temple’s short stone walls wear an ancient forbidding gloom that keeps us at a wary, but respectful, distance.

The air is sweet, the grass soft, the ground is pregnant with rainwater, it sweats and darkens my toes when I step on it. I don’t mind, it’s not a cow pat. There are many – they somehow belong there as much as the stones that the Toda use to mark their temple grounds.

A gnarled tree stands in the middle of the village grounds – Chief tells us it is called the Snake Tree. He doesn’t explain much about why, but he says it is an old, old tree that is worthy of respect. Below this tree is The Rock.

Chief says, Young men in this village lift this to prove their strength. Go on, young men – try it.

The boys try – grunts, swears (softly, in case Chief hears it), growls, sudden jerks, to no avail. The Rock rolls around on the grass tauntingly, not even a millimeter above the ground. The blades of grass under it are still squashed flat, not a single one has unbent.

Chief says, The trick is to roll it into the right position in the cradle of your arms, then you stand up. He says this with a straight face, so it must be the way, but you can’t help but think behind that moustache, his lips were curving slightly in amusement.

The boys try again – the swears are not so quiet now, the grunts a bit louder, the jerks a bit harder. Friendly advice from bystanders about hernia were ignored. The girls were biting their lips to not laugh at the noble effort at machismo. The Rock rolls around a bit more. Some blades of grass unfurled slightly under the rock, but it still was no more than a centimeter off the ground, for a nanosecond.

The boys stood, chests puffing with exertion, shaking their heads. Chief walks up, and demonstrates the correct position, smoothly, quietly. He doesn’t lift The Rock, he says he is too old and he doesn’t want to get hurt. But one can see he has done this before in his youth. The stance, the familiar way he touches The Rock. He looks at the boys, probably 20 years his junior, and speaks with a quiet pride. Young men in his tribe have been able to lift The Rock so easily that the village elders have taken to buttering The Rock to make it more challenging.

The boys were still digesting this fact in stunned silence. I ask, half-joking. Is there a remedy that the Toda have for back pain?

Chief says, through translation. It is our women’s responsibility to take care of their men.

I think I was just put in my place.

Chief has done so with that same quiet dignity that he has carried through our entire visit. His wife had done so with the pride in their heritage when she discussed her work with a joint Japanese-Indian study to preserve the Toda dialect. His aunt had done so when gracefully permitting us to take a picture of her face unadorned with artifice, but lovely lined with character and age.

The Toda embodied a quiet dignity that seemed to be at peace with the universe. Somehow perfectly in place, at home.

In the Nilgiri mountains within the Tamil Nadu district of South India, there live a people that date themselves back to the conquering heroes of Alexander the Great and the Macedonians.

They speak a language that has lilting tones and sibilant sounds that are strangely reminiscent of the Lakota nation in North America. They wear their hair in single or double plaits, drape hand-embroidered shawls like the Romans of old, and worship the buffalo. They revere nature and abhor warrior-like activities, but live in a small but communal world where a woman can be a wife to many men, and a man can be a husband to many women.

These are the Toda people. They are indigenous to these hills. Despite seeing their own leave their community boundaries and never return, despite watching a population age and their kind dwindle down to around 1,500 people, they still walk erect with pride and do not forget their stories and teachings of old. They speak Tamil to outsiders, tell them of the Toda heritage, but speak to each other in their own secret language that echoes their unique identity that they are still fiercely trying to protect.

Chief tells us, in his deep voice, that there are not many Toda left.

Many young people have left, to pursue what they think is a better life outside their village boundaries.

Many young people have left, to pursue what they think is a better life outside their village boundaries. But don’t they keep in touch? Visit you?

Once they leave us, they have left us forever.

It is sad that there is no turning back. I imagine I heard in his voice, in the strong yet quiet voice of this village headman, that it breaks his heart when they leave, because he knows how hurtful it is to not be part of your people anymore, how painful to see them outside and treat them no more than strangers.

Their homes feature an elliptical roof – historically because the Toda would bend the flexible reeds and branches to make roofs, and has since become an architectural feature unique to their people. Their homes are now concrete, a modern convenience that still pays homage to their simple lives by being no bigger than a shipping container.

When Chief invited us inside, we stepped in barefoot quietly in reverence. He showed us with pride, pictures of his family, his people – some living in other areas of India, gathering for tribal celebrations in their full regalia. Some of these pictures were old and dogeared. Others were clearly pictures taken by visitors that were left with him as momentos.

He took pains to explain each picture – this is a marriage ceremony, this man is a chief over in this other village. The words were few, but the feelings ran deep. I imagine this man knows in his heart that he could be the last of his family to still have 30-year-old pictures of millennia-old rituals, explaining age-old customs to young visitors.

The walls were solid and smooth, yellowed and bare, except for faded pictures in old frames, and the symbol of the buffalo horn, placed high in a position worthy of respect. There was a bleak sadness to this spartan house – but you couldn’t help but be filled with admiration for the dignified way Chief, and his wife, speak of their people, their efforts to survive, and live meaningfully to preserve their heritage.

The small house opens into a spacious cement frontyard, where Chief’s aunt (I think) smiles at us. An irresistible photo opportunity.

The front yard was the start of the true world of the Toda – green fields marked by solitary stones, holy spiritual space bound by pieces of ancient rock. It’s okay, says Chief. Female non-believers can walk past the stones, we do not mind. Toda women know to stay outside these rocks.

There are two temples, probably musty with old on the inside, full of mystical and ancient energies that are shut behind stone walls with hand-carved symbols of the sun, the moon and the stars. We do not get too close – Chief says non-believers are not permitted past the rock wall immediately surrounding the small temple. We don’t get closer – the temple’s short stone walls wear an ancient forbidding gloom that keeps us at a wary, but respectful, distance.

The air is sweet, the grass soft, the ground is pregnant with rainwater, it sweats and darkens my toes when I step on it. I don’t mind, it’s not a cow pat. There are many – they somehow belong there as much as the stones that the Toda use to mark their temple grounds.

A gnarled tree stands in the middle of the village grounds – Chief tells us it is called the Snake Tree. He doesn’t explain much about why, but he says it is an old, old tree that is worthy of respect. Below this tree is The Rock.

Chief says, Young men in this village lift this to prove their strength. Go on, young men – try it.

The boys try – grunts, swears (softly, in case Chief hears it), growls, sudden jerks, to no avail. The Rock rolls around on the grass tauntingly, not even a millimeter above the ground. The blades of grass under it are still squashed flat, not a single one has unbent.

Chief says, The trick is to roll it into the right position in the cradle of your arms, then you stand up. He says this with a straight face, so it must be the way, but you can’t help but think behind that moustache, his lips were curving slightly in amusement.

The boys try again – the swears are not so quiet now, the grunts a bit louder, the jerks a bit harder. Friendly advice from bystanders about hernia were ignored. The girls were biting their lips to not laugh at the noble effort at machismo. The Rock rolls around a bit more. Some blades of grass unfurled slightly under the rock, but it still was no more than a centimeter off the ground, for a nanosecond.

The boys stood, chests puffing with exertion, shaking their heads. Chief walks up, and demonstrates the correct position, smoothly, quietly. He doesn’t lift The Rock, he says he is too old and he doesn’t want to get hurt. But one can see he has done this before in his youth. The stance, the familiar way he touches The Rock. He looks at the boys, probably 20 years his junior, and speaks with a quiet pride. Young men in his tribe have been able to lift The Rock so easily that the village elders have taken to buttering The Rock to make it more challenging.

The boys were still digesting this fact in stunned silence. I ask, half-joking. Is there a remedy that the Toda have for back pain?

Chief says, through translation. It is our women’s responsibility to take care of their men.

I think I was just put in my place.

Chief has done so with that same quiet dignity that he has carried through our entire visit. His wife had done so with the pride in their heritage when she discussed her work with a joint Japanese-Indian study to preserve the Toda dialect. His aunt had done so when gracefully permitting us to take a picture of her face unadorned with artifice, but lovely lined with character and age.

The Toda embodied a quiet dignity that seemed to be at peace with the universe. Somehow perfectly in place, at home.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home