Helpless

I hate hospitals. It doesn't matter how good a reputation it has, how much good care it provides its patients, how human the atmosphere. Hospitals give me the willies, because everytime I step into one, I am reminded that so much of human life is outside human control, yet in the hospital I am confronted with the futile effort we make to prove otherwise.

She has been in the hospital since Sunday. This was not the first time she has been hospitalized, but it is the second admission in these few weeks. I went to see her, because it's been many months since I've had more than a few days to spend in this city. I go after work, arriving during the tail end of visitors' hours.

My leather pumps are clacking against the waxed clean vinyl floors, the sounds echoing off the walls. I take comfort in my brisk tread, a charade of control in a place where human lives are fighting against disease, old age and death.

I arrive at her bed, and she is awake. Her head turns towards me, because she still has her sense of curiousity behind the veil of dementia. Her eyes flicker, and I think she may have recognized me. I call her, she nods in acknowledgement, but I know deep down that the nod is automatic. The same nod she would accord a complete stranger, not her granddaughter, the same girl that spent almost every weekend of her childhood years playing with her grandmother.

Her caretaker is cajoling her to take a sip of the nutrition supplemental drink. The plastic cup is pushed against her gnarled fingers, she opens them and pushes the cup away. Her body may not know its hungry, but it still knows that it doesn't want to be told what to do. Her independence and stubborn streak don't hide behind illness - they are defiant and remind us that this is a woman with spunk. Yet defiance and stubborness don't make her hands grip, they don't make her spindly legs stronger, and they don't make the cancer cells disappear.

Those legs that used to chase after grandchildren, while she yelled after the kids to behave themselves. The same hands that would peel all fruits meticulously because of an irrational belief that the rot hides under the peel. The fingers that can no longer hold on to a cup, used to pound chili and dried shrimp in a heavy stone mortar. She used to call after me to eat up, now I am coaxing bits of moistened bread into her mouth.

Go on, I said. You're hungry, you must eat. Look, it's bread with jam, your favorite. Go on, it's good.

White bread with grape jelly, poor fare compared to the spread she used to be able to whip up. Her voice used to be sharp when chastising naughty kid fingers attempting to pick at food before it was ready. It used to coax us to sleep when we were too tired after play but too stubborn to nap. It would laugh in praise when we were able to show we could count the number of plastic toys she bought for us. It would be quiet with pride that she knew how to write her name and the numbers 1 to 10, despite not being able to write much else.

She moves her dry lips feebly, I don't hear anything but I know she knows I am there. I know she says hello. I touch her wrinkled and bony hands, the skin delicate like spiderwebs. There are marks from when the intravenous drip was inserted -- red marks that stood out harshly against her paleness.

I hold my lips steady. She never approved of crybabies. She preferred to use her energy fighting, scolding, than sobbing. She is one of the most stubborn, irrational, strongest, obstinate women I know. She may have surpassed the doctor's expectations, but the toughest test is yet to pass.

It's no use, she won't drink her supplement, nor eat her piece of bread. Cause and effect have disassociated themselves in her head - hunger no longer equals ingesting food. She's tired, she's had enough of these people hovering over her. Her arms slowly but surely fold themselves on her chest, a vague parody of her old obstinate stance. She closes her eyes, her lips imperceptibly tighten and her medicated-swollen cheeks seem slightly more clenched.

We get her point, she's ready to sleep. No more supplements, no more bread, no more babying and cajoling and noise and shadows. Leave her to her little world where the next thought is as confusing as the one before, and all she wants is to rest. I pat her hand - she ignores me.

Good night, Grandma. You're cold, here's a blanket. Let me turn down the fan. I'll see you tomorrow, okay?

I turn and leave. I bite my lip. I walk slowly and try to be quiet so my clicking high heels don't wake any of the other patients, all geriartric women, some calling out in their sleep, others curled into the fetal position they were born in. A chilling reminder that we can die as helpless as we were born. I look back, and she is asleep. I don't know what she remembers, or what she is seeing in her dreams. I know that I remember too much, and I can't let her go. I also know that I am helpless.

This is the reason I hate hospitals.

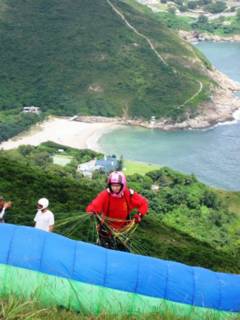

Grandma and my brother

She has been in the hospital since Sunday. This was not the first time she has been hospitalized, but it is the second admission in these few weeks. I went to see her, because it's been many months since I've had more than a few days to spend in this city. I go after work, arriving during the tail end of visitors' hours.

My leather pumps are clacking against the waxed clean vinyl floors, the sounds echoing off the walls. I take comfort in my brisk tread, a charade of control in a place where human lives are fighting against disease, old age and death.

I arrive at her bed, and she is awake. Her head turns towards me, because she still has her sense of curiousity behind the veil of dementia. Her eyes flicker, and I think she may have recognized me. I call her, she nods in acknowledgement, but I know deep down that the nod is automatic. The same nod she would accord a complete stranger, not her granddaughter, the same girl that spent almost every weekend of her childhood years playing with her grandmother.

Her caretaker is cajoling her to take a sip of the nutrition supplemental drink. The plastic cup is pushed against her gnarled fingers, she opens them and pushes the cup away. Her body may not know its hungry, but it still knows that it doesn't want to be told what to do. Her independence and stubborn streak don't hide behind illness - they are defiant and remind us that this is a woman with spunk. Yet defiance and stubborness don't make her hands grip, they don't make her spindly legs stronger, and they don't make the cancer cells disappear.

Those legs that used to chase after grandchildren, while she yelled after the kids to behave themselves. The same hands that would peel all fruits meticulously because of an irrational belief that the rot hides under the peel. The fingers that can no longer hold on to a cup, used to pound chili and dried shrimp in a heavy stone mortar. She used to call after me to eat up, now I am coaxing bits of moistened bread into her mouth.

Go on, I said. You're hungry, you must eat. Look, it's bread with jam, your favorite. Go on, it's good.

White bread with grape jelly, poor fare compared to the spread she used to be able to whip up. Her voice used to be sharp when chastising naughty kid fingers attempting to pick at food before it was ready. It used to coax us to sleep when we were too tired after play but too stubborn to nap. It would laugh in praise when we were able to show we could count the number of plastic toys she bought for us. It would be quiet with pride that she knew how to write her name and the numbers 1 to 10, despite not being able to write much else.

She moves her dry lips feebly, I don't hear anything but I know she knows I am there. I know she says hello. I touch her wrinkled and bony hands, the skin delicate like spiderwebs. There are marks from when the intravenous drip was inserted -- red marks that stood out harshly against her paleness.

I hold my lips steady. She never approved of crybabies. She preferred to use her energy fighting, scolding, than sobbing. She is one of the most stubborn, irrational, strongest, obstinate women I know. She may have surpassed the doctor's expectations, but the toughest test is yet to pass.

It's no use, she won't drink her supplement, nor eat her piece of bread. Cause and effect have disassociated themselves in her head - hunger no longer equals ingesting food. She's tired, she's had enough of these people hovering over her. Her arms slowly but surely fold themselves on her chest, a vague parody of her old obstinate stance. She closes her eyes, her lips imperceptibly tighten and her medicated-swollen cheeks seem slightly more clenched.

We get her point, she's ready to sleep. No more supplements, no more bread, no more babying and cajoling and noise and shadows. Leave her to her little world where the next thought is as confusing as the one before, and all she wants is to rest. I pat her hand - she ignores me.

Good night, Grandma. You're cold, here's a blanket. Let me turn down the fan. I'll see you tomorrow, okay?

I turn and leave. I bite my lip. I walk slowly and try to be quiet so my clicking high heels don't wake any of the other patients, all geriartric women, some calling out in their sleep, others curled into the fetal position they were born in. A chilling reminder that we can die as helpless as we were born. I look back, and she is asleep. I don't know what she remembers, or what she is seeing in her dreams. I know that I remember too much, and I can't let her go. I also know that I am helpless.

This is the reason I hate hospitals.

Grandma and my brother